Videoverse review

As people of a certain age will know, the current, slow-moving death of Twitter is nothing we haven’t seen before. Most of us who were knocking around the internet in the early 00s will have at least one online gravestone in the closet somewhere, whether it’s a long abandoned LiveJournal or MySpace page, or an old internet forum that sadly doesn’t exist anymore (RPS in peace). But for the citizens of Videoverse, an online community that’s part and parcel of the soon to be defunct 1-bit video games console the Kinmoku Shark, this sense of an ending is something that many of them aren’t equipped to deal with, least of all teenager Emmett, who’s just discovered the fan page for his favourite video game, Feudal Fantasy.

As he deals with the prospect of having to bid farewell to friends old and new, including the mysterious but talented fan artist Vivi, Videoverse taps into a potent and nostalgic melancholy. It’s a love letter to the early internet at its rose-tinted best, and to the lost, formative spaces that brought so many like-minded individuals together and gave them a sense of purpose. Yes, there are trolls spoiling everyone’s fun, and yes, there’s a hint of something more nefarious going on underneath Videoverse’s source code. But another Hypnospace Outlaw this is not. Rather, this is a proto-internet tale that’s all about the friendships we form online, and the bonds that carry us forward when real-life relationships just don’t cut it anymore.

Most of your time in Videoverse is split between three main activities. The Shark is, of course, a video games console first and foremost, and when Emmett logs on each day, we’re treated to snippets of Feudal Fantasy’s beautifully crafted 1-bit cutscenes. As Emmett progresses further in this ninja-infused riff on Final Fantasy, these story beats provide the necessary context for his second favourite activity: chatting with fellow FF likers on the Shark’s Videoverse forums.

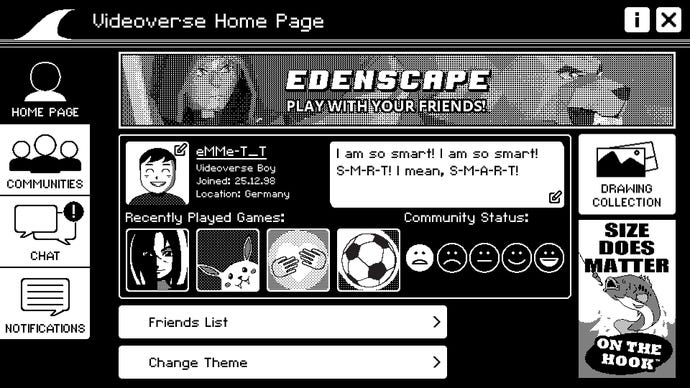

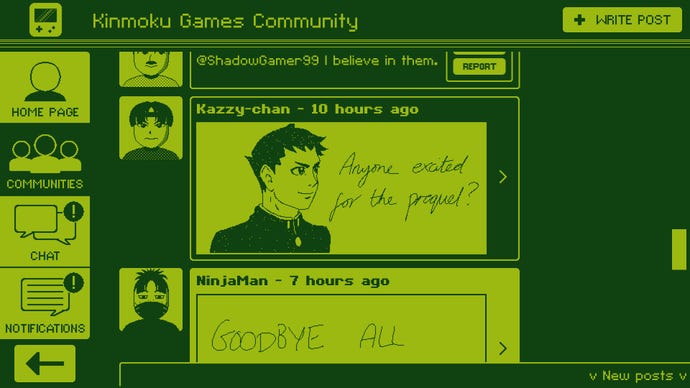

Like Hypnospace, Videoverse is split into pages that you can dip in and out of at will like an internet browser. Everyone has their own home page you can visit, and a notification menu will collate all the replies and comments you receive on the posts you make. Unlike Hypnospace and its ever-expanding warren of weirdness, however, there are just four main community pages you’ll be interacting with here: the official Kinmoku noticeboard, an Off-Topic community, Art Corner, and that all-important Feudal Fantasy page. The latter is where Emmett will post his fan art and interact with other fans, but you can like and reply to comments across all four of these communities as much or little as you please.

Doling out likes doesn’t have too much of an impact on the tone or growth of Videoverse as a whole, admittedly (bar unlocking some extra colour themes for your console), but the responses you choose to certain posts and comments will gradually shape how these pages evolve over time. Reporting trolls and being supportive of other users in trouble might not seem like much in the moment, for example, but Videoverse juggles its dozen-odd narrative threads with a deft and expert hand, weaving them into an authentic tapestry of online drama that delivers satisfying payoffs for those curious enough to see them through to their conclusions.

In this sense, Videoverse reacts to your presence just as successfully as Hypnospace does, albeit from the perspective of a regular user rather than an online corpo cop. But whereas Hypnospace guides you from one discourse fire to the next, Videoverse feels a lot more organic in how you’re able to interact with it. While each of these ‘Help Out’ tasks is handily logged in a notebook on Emmett’s desk that you can thumb through at any time, you’ll need to put in the time and attention to keep track of these budding story threads as the game goes on. If you miss a pertinent post or just forget to visit the community page one day, they might slip through your fingers entirely, or get subsumed in the growing paranoia about Videoverse’s closure. None of them are necessary to ‘complete’ Videoverse, so to speak, but its emphasis on active participation makes for a more elastic and intimate-feeling space than the halls of Hypnospace – which is impressive considering its simple layouts and 1-bit colour palette lack the immediate visual fingerprints of the latter’s scrappy Geocities homage.

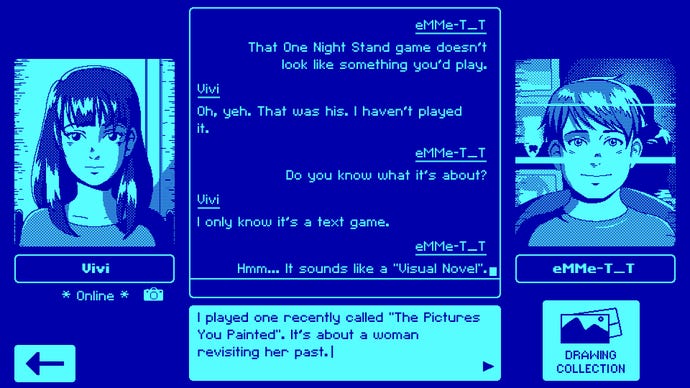

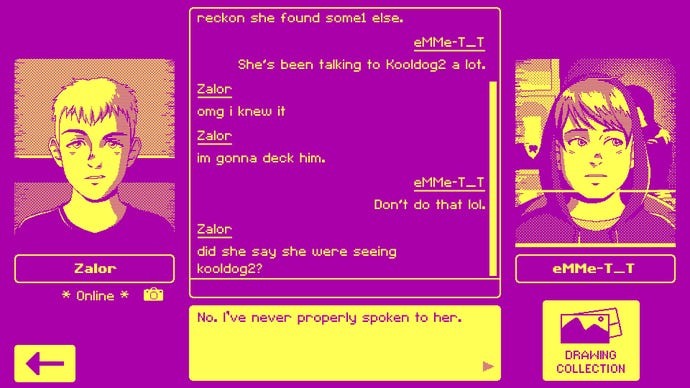

But the real star of Videoverse is its MSN-like chat windows. It’s here where the bulk of the game’s story plays out, and where you’ll have the greatest impact on the lives of your online pals. Regional accents, online slang, emoticons and hurriedly deleted and retyped messages all work together to paint an accurate picture of those early online messaging days, as do the low-res webcam reactions of your closest inner circle. Once again, you’ll be using the game’s dialogue options to further your relationships with these folks, and taking the time to help them out with their various problems has a similarly pronounced effect on how those friendships develop over the course of the game.

But Videoverse also knows that some problems can’t really be solved with easy, gamifiable checklists. Its greatest triumph is capturing that sense of helplessness that comes from knowing there’s something deeply wrong with the person you’re talking to on the other side of your screen but are in no position (or indeed the right country) to really help them – where the lesson isn’t so much about saying the right thing (thought that will, of course, help), but in simply being a good human.

This tension is played out beautifully in Emmett’s blossoming friendship with Vivi, a new FF community member whose amazing artwork hides a profound sadness and personal tragedy. As the pair grow closer and bond over their shared love of fan art, Emmett desperately wants to make things better for Vivi, but his own immaturity and lack of awareness means he’s constantly sticking his foot in it. Combined with the ever-looming threat of losing her forever in the wake of Videoverse’s closure, and there are real, tangible stakes in this relationship that pull hard on the old heartstrings. It makes each dialogue choice feel that much more momentous and important, and navigating these messy, delicate exchanges through its low-tech chat logs is Videoverse at its best.

There are real, tangible stakes in this relationship that pull hard on the old heartstrings.

It’s wonderfully done, although I do wish the climax of your breakthrough with Vivi relied less on parroting other users’ words of ‘Videoverse wisdom’ Emmett can note down through the game, and more on his own maturing realisations. Strangely, selecting the former does feel right in the moment (and is marked up to feel like an appropriate reward for taking the time to notice these sagely nuggets in the first place), but in hindsight it can’t help but feel a little jarring to me. There’s so much that comes straight from the heart in Videoverse, from its sensitive discussion and portrayal of disability to its clear love for all things fandom and the early 00s, that to suddenly rob Emmett of making that final leap in his own personal growth arc himself feels a touch heavy-handed.

Still, it’s hard to stay mad too long when Clark Aboud’s increasingly sorrowful score does such a good job of wrestling you into emotional submission. Not only does it beautifully reflect Emmett’s own despondency and the general growing gloom around Videoverse’s demise, but there’s also a moment in that final confrontation scene where it pulls the rug out from under you so effectively that you can’t help but take a beat to applaud it.

Taken together, Videoverse is strong, powerful stuff that leaves a deep and tender impression, building on the same fascination with the perils of human intimacy as developer Kinmoku’s previous game, One Night Stand, but on a much more impressive scale and accomplished canvas. Part of its appeal may well play on that nostalgia for a bygone era of social networks, but its beautifully observed cast of characters and interpersonal dramas make this a much more universal and compelling take on early interneting than Hypnospace Outlaw could ever dream of. There’s a lot more to latch onto here, and so let it be known: the campaign for Videoverse to be the one true Twitter replacement starts here.

This review was based on a retail build of the game provided by the developer Kinmoku.

fbq('track', 'PageView'); window.facebookPixelsDone = true;

window.dispatchEvent(new Event('BrockmanFacebookPixelsEnabled')); }

window.addEventListener('BrockmanTargetingCookiesAllowed', appendFacebookPixels);